Working in Maine

Most people approach Maine from the south, following route I-95 through New England and crossing the Piscataqua River at Portsmouth, New Hampshire. For the first hour of the drive in Maine, one passes the coastal communities of York, Wells, and Kennebunkport, quiet towns that explode in the summer as southern New Englanders escape from the heat to Maine's beaches. I-95 continues north into Portland, Maine's largest city with an eclectic fusion of historic and modern. Here is where we alter our journey, eschewing the highway for coastal Route 1.

Within a few brief miles, the landscape changes from urban to decidedly rural. As one travels through the fishing villages and tourist towns that pepper the coastline, time itself seems to slow. This is a part of Maine that has been shaped by glaciers, waves and wind; it has eroded into an endless array of islands and bays, peninsulas and coves. Its harsh weather and severe topography are tempered only by its fragile beauty. Some three hours and 150 miles later, we arrive at the midcoast region, otherwise known as Downeast Maine. It is here that we have chosen to live and practice architecture.

Along this rocky coast, among the blueberry fields and spruce forests, we find inspiration for our work, seeking the exceptional in the everyday. A dappled sunlit view of a meadow path, a breeze laden with the sweet smell of the sea, ever changing patterns of light dancing off water: these are magical moments we seek to frame through an architecture that turns attention away from itself. There have been many influences for us over the years, but the defining factor in our firms work has always been practicing architecture in Maine, amid ordinary and extraordinary beauty.

Maine is not at the center of any architectural movement. It is not a place that looks to stand out or make a statement. Nor is it the kind of place where you casually end up. Instead, Maine is a place that draws people in, allowing for discovery, and they either end up loving it or abandoning it. We have come to love Maine. We love the sound of waves crashing against rocks at Schoodic Point, the silence of a spruce forest on a snowy morning, and the brilliant red of the blueberry fields in the fall. We admire the inclusiveness of a town meeting, where item by item we all vote by a show of hands. We enjoy escaping for a hike in the woods or a solitary kayak paddle along the rocky coast. But we have also learned to respect Maine and its environment, where wind can blow so hard that rain is driven sideways, where several feet of snow can fill the dooryard in mere hours, and where impenetrable fog can silently encapsulate the shore without warning. We accept that spring is replaced by mud season and that blackflies and mosquitoes are not to be ignored. The author Robert Heinlein once wrote "Climate is what we expect, weather is what we get." This has never been more true than in Maine.

From this we have learned the necessity of building well. Living here, we have grown to know and love the simple, humble buildings of our state: the grange halls and barns, the wharf buildings and the mills. We love them not merely for their beauty, but because they are still here. They have withstood countless winters, myriad storms, and ever changing weather. Beneath the surface of their seemingly mundane details lies an innate understanding of the Maine climate. It is in the relationship between the state's natural beauty and the historic fabric it supports that we find constant inspiration for our work.

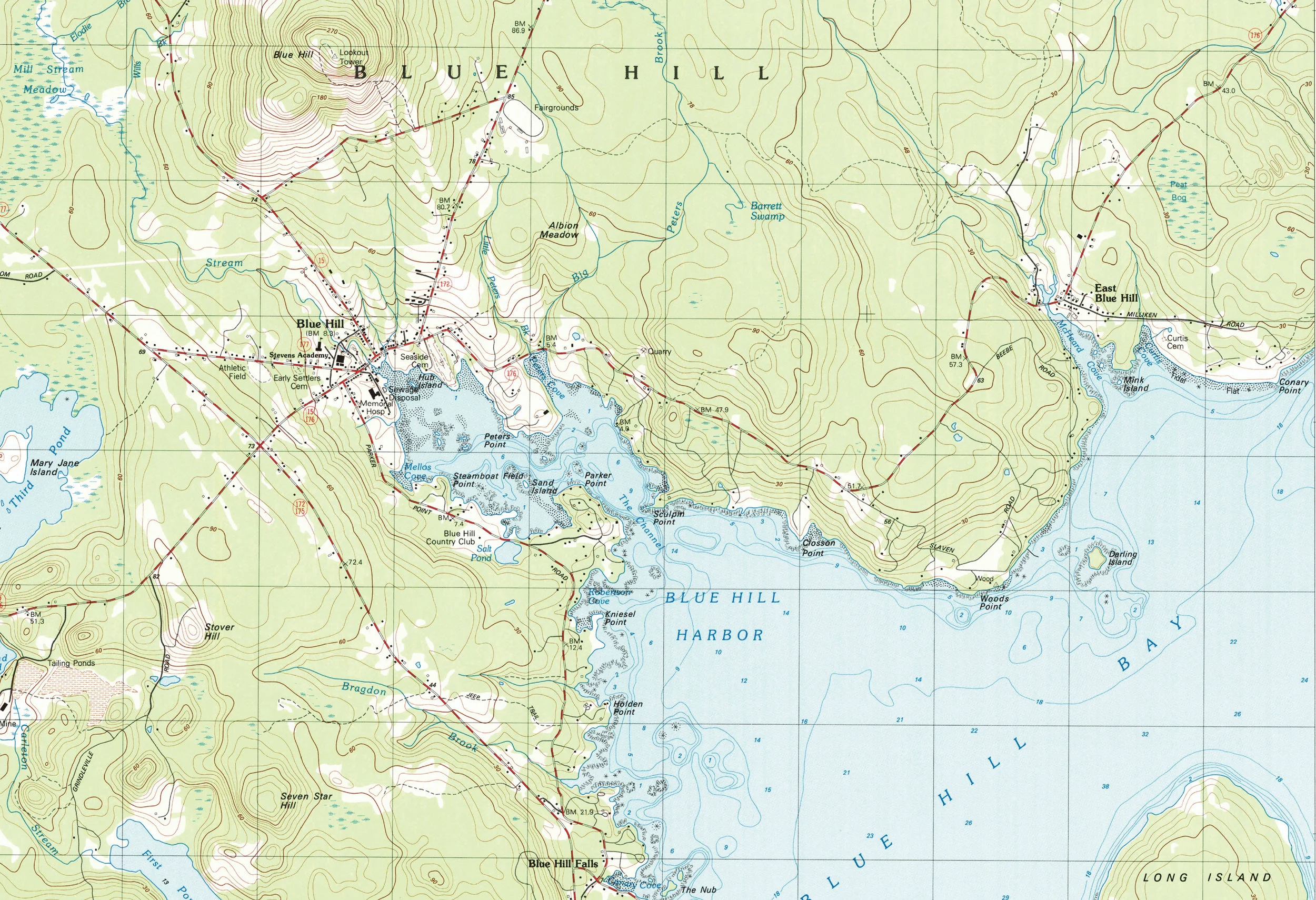

At the bottom of the hill on Pleasant Street, a T intersection marks the middle of the town of Blue Hill. To the right is the local garage, where a row of cars sits outside, waiting to be worked on. Ahead is Masonic lodge #128, and to the left is a white-clapboard Greek Revival house with a wide wraparound porch. It is in this house, built in 1835, that our offices are located. At the rear of the building, a connected barn is slowly settling into its years and into the site. By contrast, the attached ell and the main house, which sit on granite blocks cut from local quarries, have held steadfast and will remain here for generations to come.

The building began its life as the residence of a prominent local merchant, and it has a history as varied as Blue Hill itself. Before it was our office, the house was at different times home to the local telephone company, a restaurant, and an art gallery. Over the years it has been renovated and revised, added to and subtracted from according to the needs of its inhabitants. When we first saw the classic building, we fell in love with it— realizing that we would have the opportunity to write its next chapter.

We have adapted the house to our needs, creating an environment for a collaborative architectural practice. The main work space, directly off the front porch, has four large tables in the center of the room, each made from a single piece of ash. These tables are constantly ensconced beneath drawings, material samples, and models as we struggle with a particular project. There are no cubicles or corner offices; there is no hierarchy or separation—just one large studio space that we all inhabit equally. Working this way does incite a bit of chaos (what we like to call energy), but it also invites ongoing collaboration and ensures that even when we are busy with our own individual projects, we are always aware of the larger environment around us. This is the space that brings us together—clients, consultants, builders, and employees alike–both physically and philosophically.